A Linux Alternative? Debian/hurd Shows Microkernel Unix Dream Is Alive

Before Linux, GNU was working on its own Mach-based Unix compatible OS. Now, in the footsteps of Debian 13, there is a new release.

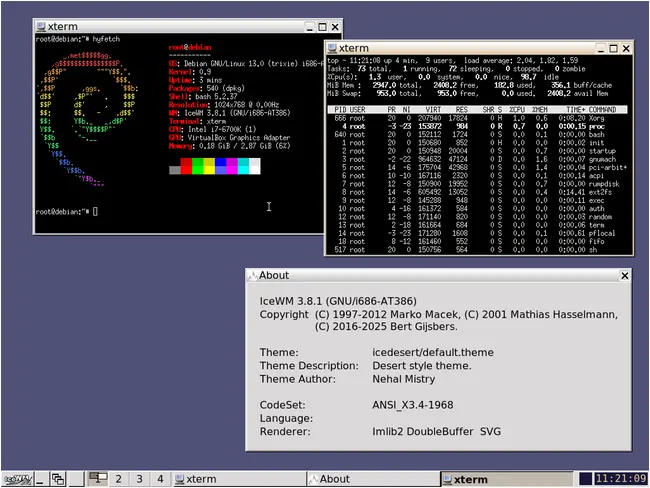

Debian GNU/Hurd 2025 is the latest release of the other GNU operating system. The announcement email from developer Samuel Thibault says this release includes a working x86-64 edition, thanks to NetBSD disk drivers in a Rump layer – which also means it can now use USB disks and CD drives. Hurd has a port of the Rust language, plus “quite working” SMP support, and it can run “about 72% of the Debian archive, and more to come!” It’s the first news update from the project since June 2024, and clearly significant progress is happening. The activity trend line looks good.

This is not exactly a review, because this is not exactly an alternative Unix OS. The Hurd is not any form of Linux, nor is it a BSD. So, although Debian GNU/Hurd 2025 is an edition of Debian Trixie, bear in mind that this is a highly-experimental OS, built to a radical design. It doesn’t run on many different models of hardware, and it won’t run most existing software. Its readme file is called YES_REALLY_README, and it opens as follows:

Foreword ******** https://xkcd.com/293/

GNU/Hurd is not Linux.

https://darnassus.sceen.net/~hurd-web/faq/

Please do read this README to know what you really need to know before trying GNU/Hurd.

The line that says Hurd is not Linux is really important. The Hurd is an experimental OS for people interested in studying OS design and implementation. In that way, it’s similar to 9front, the fork that continues development of Plan 9. One of the first entries in 9front’s equivalent to an FAQ page says: Plan 9 is not for you. It continues:

Let’s be perfectly honest… If you cannot imagine a use for a computer that does not involve a web browser, Plan 9 may not be for you.

That applies here too. If you know what the Hurd is, and you’re interested in OS research, this is a fascinating new release. If, on the other hand, the questions that come to your mind are Can I run interesting or fun things on it? or Can it replace Windows? or Will it work on my computer? then the answer is “no.”

It is a form of Debian, but only in a fairly loose sense that most Debian users are not aware even exists: Debian is not only a Linux distribution. As well as Debian GNU/Linux, there are also other flavors of Debian which use different kernels and so are not Linuxes at all.

Debian was launched almost exactly 2⁵ (that’s 2^5 – meaning 32 – not 25) years ago. Two years ago this month we celebrated its 30th anniversary. As we mentioned in that article, there was a time when the GNU project seriously evaluated adopting the BSD kernel from 4.4-BSD Lite.

If it had done so, a complete working GNU OS could have appeared before Linus Torvalds started work on the little hobby project he announced in August 1991:

Hello everybody out there using minix –

I’m doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won’t be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones. This has been brewing since april, and is starting to get ready.

But GNU/BSD never happened. Instead, around the time that Linus started work in April 1991 — meaning months before he told anyone about it — the GNU project chose not to use the BSD kernel. Instead, in May, it announced that it would write its own OS:

The Free Software Foundation is beginning work on a GNU operating system built on top of the Mach 3.0 microkernel.

At the time, the Mach project was the state of the art in microkernel design. Today, Mach is the basis of the XNU kernel used in macOS and iOS. In the past, Mach was also the basis of the Open Software Foundation’s OSF/1 which was the basis of Digital UNIX, later renamed Tru64. Before the NeXT merger, Apple used it in MkLinux, one of the first ports of Linux to PowerMac hardware.

The GNU Hurd project still continues today, and it still uses Mach. Today, gnumach is up to version 1.8. The project maintains a history page detailing its development. In recent years, updates sometimes reached quarterly frequency, which the project calls QoTH bulletins – the Quarter of the Hurd.

Debian has been in continuous development for 32 years, and in that time, there have been several editions that ran the Debian userland on top of other kernels. In other words, there are Debians that are not Debian GNU/Linux.

Debian GNU/kFreeBSD used the Debian userland on top of the FreeBSD kernel, although sadly, due to lack of manpower the project ended in 2023. There was a similar effort using the kernel from the slightly older BSD, Debian GNU/NetBSD. Multiple others have been suggested, including ports to the kernels of OpenBSD, OpenSolaris, IBM’s OS/2 kernel and others.

The Reg FOSS desk rather likes the sound of Debian GNU/kOpenSolaris, or Debian GNU k/Illumos as it would probably be called today. The closest thing we’ve heard about to Debian on the OpenSolaris kernel was Nexenta OS. It was renamed to Illumian and then, sadly, shut down, although Nexenta is still around.

But today, there is one very much alive and continuing Debian project that uses an entirely different kernel: Debian GNU/Hurd. That is the project that just put out a new snapshot.

The Hurd is a Unix-like microkernel OS. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, this was a hot area of OS research, but the emergence of robust native 32-bit OSes such as Windows NT and Linux stifled OS research. The NT kernel is modular and has different personalities, but despite occasional ambitious claims, it’s not a microkernel. Since it acquired NeXT, Apple’s OSes use the XNU kernel. This is based on Mach, but the way that NeXT got good performance out of Mach was by embedding a large “Unix server” (derived from BSD code) directly inside the kernel, so it’s not really a true microkernel any more either.

The Hurd hasn’t reached version 1.0 yet. Once Linux was available, most attention and effort switched to that, despite one of the most famous flamewars of all time, between the young Linux Torvalds and Andy Tanenbaum who said that “Linux is Obsolete” – in 1992.

Linux won out because it was a simple, pragmatic design: a plain old 1970s-style monolithic kernel. Essentially it’s one giant C program, with many thousands of optional sub-components which most deployments never use. Since version 6.12, still the latest LTS version, it can even interrupt itself for smoother real-time response. Linux was good enough, and that is a survival characteristic.

Microkernels are harder. Most of the OS runs in userspace, like normal applications, not in the processor’s privileged supervisor mode. That means lots of separate little code modules that must talk to each other, sending and receiving millions of messages every second to coordinate their activities. Because of the sheer volume of communications, their performance becomes a significant burden. That means that the easier and higher-performance option is either keeping it all in one giant program (like Linux), or sacrificing design purity and moving all the Unix compatibility stuff inside the kernel (like macOS and iOS).

The microkernel way lost out because it is much harder to achieve, even though, from a theoretical point of view, it’s cleaner and more elegant. There are practical wins, too. More people can cooperate more easily working on smaller, simpler, cleanly-separated modules of code. In use, because components of the OS could shutdown or crash, be upgraded or restarted, all without affecting the kernel, such systems could be much more reliable – an argument Andy Tanenbaum made 18 years ago.

Saying that, though, there are multiple microkernels out there. One commercially-successful one is Blackberry’s QNX, which first appeared in the early 1980s. However, there’s lots of activity on FOSS microkernels, as microkernel.info describes. It lists nearly 30 active projects. One is Minix 3, whose creator Dr Andy Tanenbaum won an award for it last year. Although he didn’t know about it until a decade later, Minix 3 runs deep inside the management processor of almost every Intel processor since about 2008 – meaning all Intel chips since the Core i3/i5/i7 range.

A direct successor to Mach with much faster inter-process communications was the L4 microkernel, an effort which continued past the tragically early death of project leader Jochen Liedke. The Register has covered numerous L4-based projects, most recently Neptune OS in 2022. Back in 2012, OKLabs had shipped over 1.5 billion instances of OKL4, although it looks to have dropped off since.

The point here is that there are many billions of Minix 3 and L4-based systems out there. QNX is still selling well, a decade after the end of Blackberry 10. You’d be forgiven for concluding that microkernels were a flop, a doomed academic exercise, from the narrow perspective of desktop or server OSes. It’s not the case. There are countless billions of the things out there, quietly doing their jobs without fuss, so they don’t get noticed.

Today the question of what happens to Linux after Linus retires is becoming more pressing. Kernel 6.16 appeared late last month and it’s truly vast, approaching 40 million lines of code across nearly 100,000 files. OS advocacy is eternal: we still read Windows fanboys deriding Linux as an amateur OS. Even so, this is undeniably a mature project now, with broad enterprise adoption, and as a result, it’s almost unimaginably huge.

It could be that one day, Linux will be effectively supplanted and replaced, not by something that does things better, but by something that’s just simpler, easier to understand, and more affordable to manage and maintain. Minix 3 development has gone dormant since Prof. Tanenbaum retired in 2014. We should be very glad that work is continuing on the Hurd. An all-FOSS microkernel for x86-64 PCs that can run nearly three-quarters of the packages in Debian is a great achievement. ®

A considerable amount of time and effort goes into maintaining this website, creating backend automation and creating new features and content for you to make actionable intelligence decisions. Everyone that supports the site helps enable new functionality.

If you like the site, please support us on “Patreon” or “Buy Me A Coffee” using the buttons below

To keep up to date follow us on the below channels.