Behold! Humanity Has Captured Our First Look At The Sun’s South Pole

Occupants of planet Earth can’t see the Sun’s poles – unless they look at images the Solar Orbiter spacecraft has just sent home.

The Orbiter, a joint NASA/European Space Agency project, lifted off in 2020.

The craft helped solar boffins to discover that Sol’s north and south magnetic poles are both on the southern side of the star, as seen from Earth. Scientists don’t know why and ESA rates the current state of our Sun’s magnetic field as “a mess.”

Given the Sun’s importance to life on Earth, scientists are keen to know more.

“The Sun is our nearest star, giver of life and potential disruptor of modern space and ground power systems, so it is imperative that we understand how it works and learn to predict its behavior,” said Professor Carole Mundell, ESA’s Director of Science in a statement.

Mundell hailed the photos of the poles as “the beginning of a new era of solar science.”

Earth-bound observers of the Sun can only see its equatorial regions because of our planet’s steady orbit in a flat elliptic plane. The Solar Orbiter was able to get below the equator, thanks to gravitational assistance from Earth and Venus. The probe has so far performed one Earth flyby and four around Venus, swooping in to use the planets’ gravity to adjust its speed without the need for propellant.

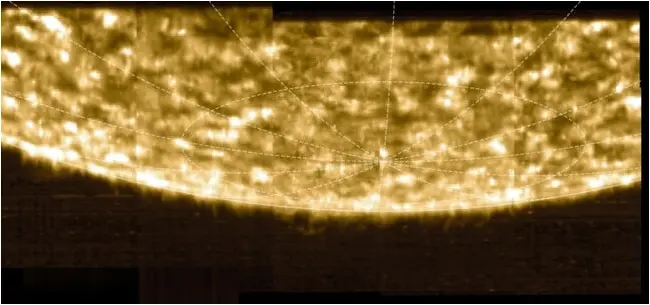

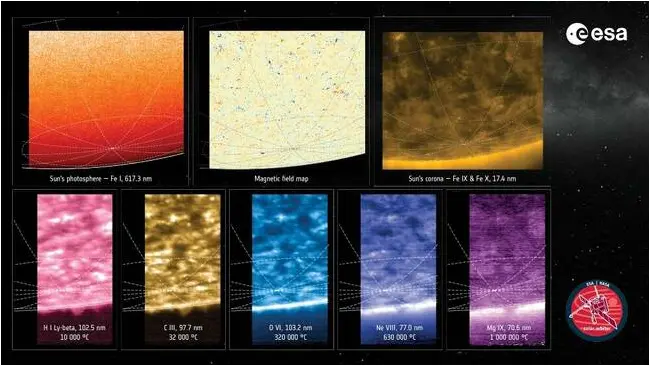

South pole of the Sun as seen by Solar Orbiter’s Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument – Click to enlarge

On February 18, the spacecraft made its closest approach yet to Venus, flying just 379km (236 miles) above the surface.

That maneuver put the probe on a course that will eventually see it orbit 17 degrees below the Sun’s equator. The spacecraft captured its first snaps from 15 degrees below the solar equator between March 16 and 17.

Solar Orbiter is arriving at an interesting time, since the Sun is reaching solar maximum. This is when the north and south magnetic poles reverse positions, which causes the star to belch out more than the usual amount of radiation and charged particles.

This is more than a little worrisome for Earth, given our electronic society’s dependence on datacenters, satellites, and other kit solar emissions could damage. We dodged a bullet in 2012 when a coronal mass ejection powerful enough to fry electronics on Earth’s surface missed us by a whisker.

By using its Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI), Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), and the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument, the Solar Orbiter spacecraft scanned the Sun to see how these magnetic changes affect such solar outbursts.

The Sun’s poles are literally terra incognita

“How exactly this build-up occurs is still not fully understood, so Solar Orbiter has reached high latitudes at just the right time to follow the whole process from its unique and advantageous perspective,” commented Professor Sami Solanki, leader of the PHI instrument team from the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany.

“We didn’t know what exactly to expect from these first observations – the Sun’s poles are literally terra incognita.”

Solar Orbiter was also able to examine the substance of the Sun’s outer shell by analyzing the composition of its upper atmosphere using the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) spectrograph. Data from that instrument should give us a better understanding of how and why the Sun spews material into space by clocking the speed of ejected star-stuff based on variations in observed color, the so-called “Doppler measurement”.

“Doppler measurements of solar wind setting off from the Sun by current and past space missions have been hampered by the grazing view of the solar poles. Measurements from high latitudes, now possible with Solar Orbiter, will be a revolution in solar physics,” predicted SPICE team leader, Frédéric Auchère from the University of Paris-Saclay (France).

NASA and ESA have collaborated before on solar research, firing off the Ulysses probe in 1990, which reached the Sun thanks to a gravitational assist from Jupiter. It managed to take readings on the solar magnetic fields, although it didn’t carry a camera. The 17-year mission involved three flybys and produced data that informed the Solar Orbiter mission.

The Solar Orbiter will make four more close encounters with Venus to adjust its course, with the next to take place on Christmas Eve 2026. It should reach a pole-to-pole stable orbit by 2030, reaching a maximum of 33 degrees below the equator.

The British-built spacecraft will then ping back data as long as its equipment – or funding – holds out. ®

A considerable amount of time and effort goes into maintaining this website, creating backend automation and creating new features and content for you to make actionable intelligence decisions. Everyone that supports the site helps enable new functionality.

If you like the site, please support us on “Patreon” or “Buy Me A Coffee” using the buttons below

To keep up to date follow us on the below channels.

![[Palo Alto Networks Security Advisories] CVE-2025-4614 PAN-OS: Session Token Disclosure Vulnerability 1 Palo_Alto_Networks_Logo](https://www.redpacketsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Palo_Alto_Networks_Logo-300x55.png)