The Masked SYNger: Investigating a Traffic Phenomenon

Where we would expect the “day interval” to simply count up from 0 (only appeared one day) to 1,2,3, etc., we see this cluster of IPs for which the Duration is between 72–74 days. Further down, we see a grouping of 52 and 53 day intervals. When do these IPs first appear and last appear?

Once we filtered on that data, we got consistent appearance of a couple very specific dates:

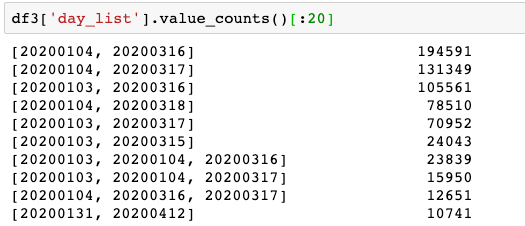

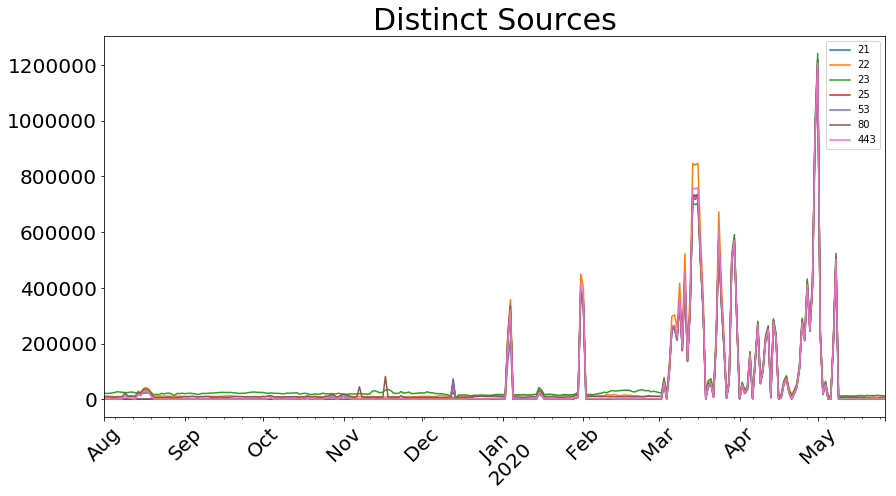

This indicates a very specific interval of appearance for the IPs seen on Jan. 3 and Jan. 4. Even though there is another spike of activity at the end of January, we do not see those IPs then. In fact we don’t see them again until until March 15.

Repeating this analysis a couple of times gives us a few intervals of reappearance:

Jan. 3, 4 → March 15,16,17

Jan 3,4 → April 14, 15

Jan. 31, Feb. 1 → March 24 and 25

March 15,16,17 → April 30 to May 2nd

This further indicates manual operation of some extent—this activity is neither purely random nor evenly distributed. While we cannot prove intent or motivation for these intervals, they are not the same length, nor do they involve the same number of addresses each time. There is some reuse for each large spike, with decreasing overlaps over time. This likely indicates some degree of human tinkering on the back end.

The signal and the noise

Finally, while most of the activity involves IP addresses used for one or two days, there are a small minority of IPs issuing huge numbers of requests, and appear on many days—but, importantly, not all days. It is possible that these IPs serve a specific purpose or that the traffic they send is in some ways different in nature than the rest of the traffic.

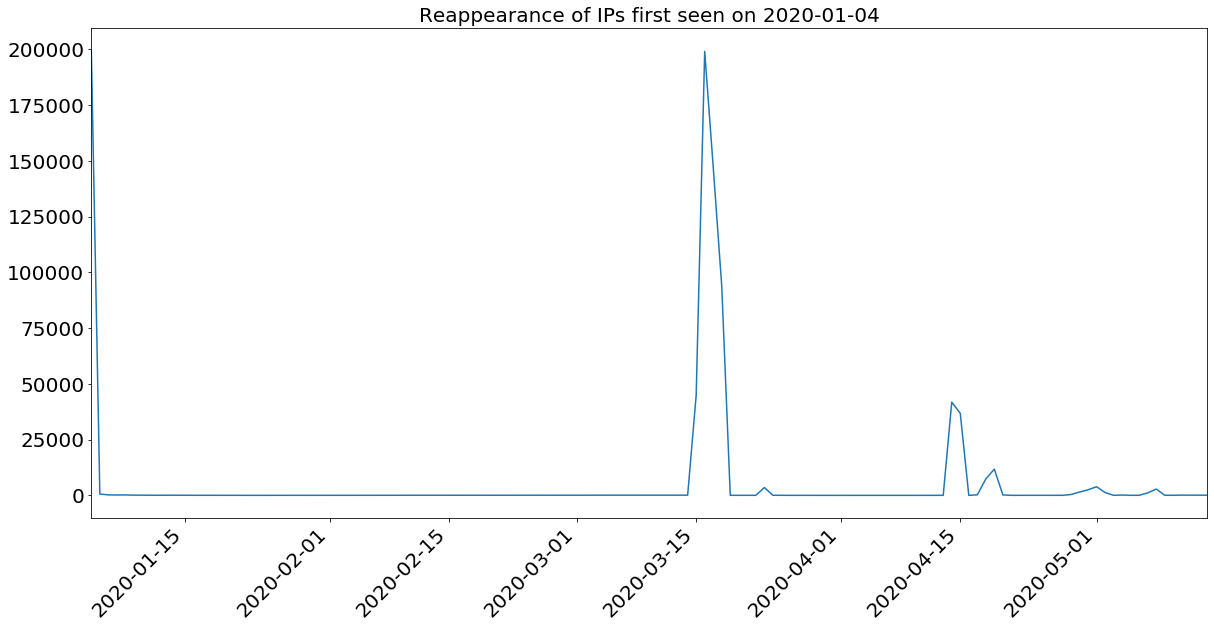

For this analysis, we focused only on traffic sent to TCP port 25 (typically used for SMTP), which resulted in the ‘S1’ conn_state, and took place between (and including) the months of January and May 2020. Focusing on a single port removed noise and reduced the dataset to something that could more easily be examined and iterated on. The same analysis should be done for other common ports seen in this traffic.

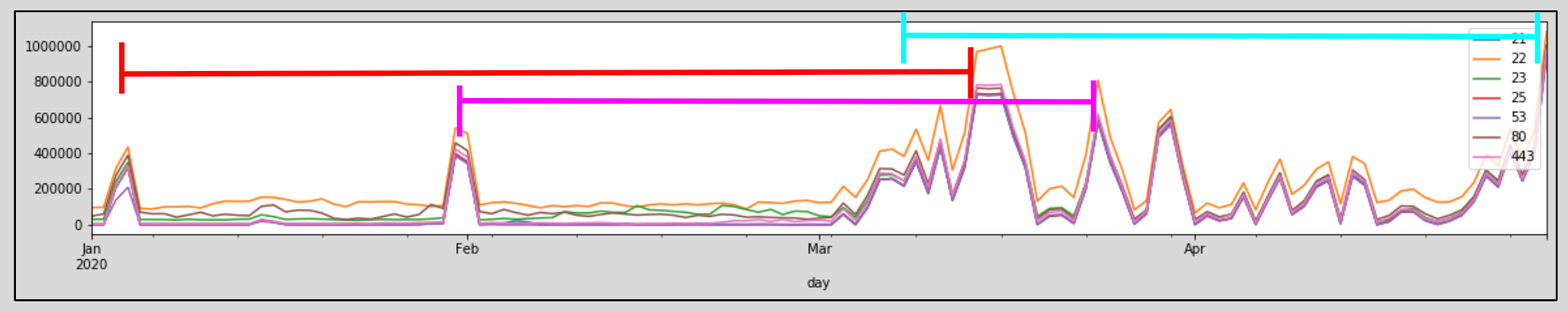

For every IP address in the data, we built a profile, including first seen, last seen, number of days total, the ‘duration’ between the first and last date, and other stats like ‘day density’ (the fraction of the duration taken by days seen). For example, an IP seen on only two days, but those days are a month apart, would have a much lower ‘density’ than an IP seen on two consecutive days.

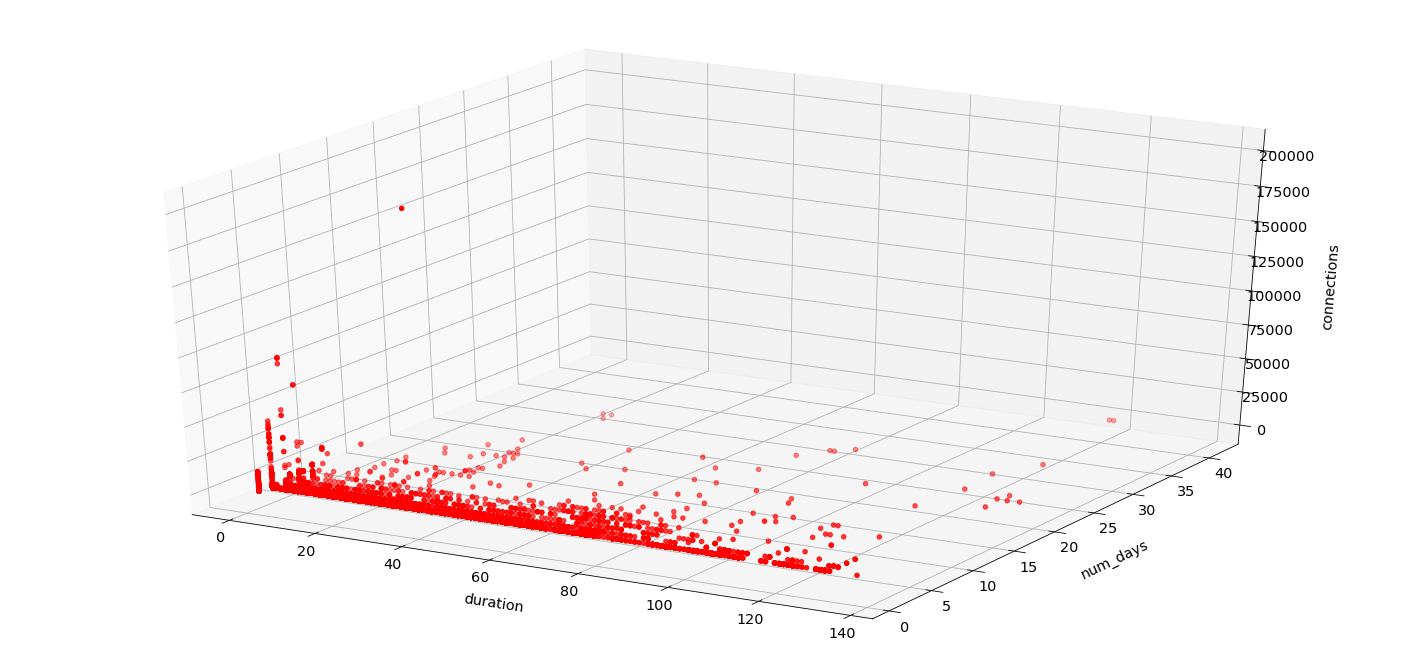

Here is the breakdown by duration and number of days:

As you can see, the vast majority of IPs exist near the bottom, each a small number (1–2) of days total. However, some of the IPs with 2–5 days have long durations—that is, the few days they appear are very spread out. Lastly, there are very few IPs with a large number of days total, over a long period of time. Let’s factor in total number of connections as well (apologies for my 3D graphing skills, I’m no @hrbrmstr):

Here, we can definitely spot one outlying spoofed source IP, the red dot near the top.

Using this approach, we are building shorter lists of interesting IP addresses to perform deeper analysis to find differences in the content. While we have been able to spot these anomalies, thus far, traffic from these “top talkers” has not substantially differed from the other packet profiles noted above. It is of course possible that the anomalies we see are strange artifacts of routing, misconfiguration, or some other factor unrelated to intent.

So what? Speculation and wildly unfounded theories

Frustratingly, we cannot point to an existing threat that we can say with any likelihood is responsible for this activity. Additionally, given our available evidence, this does not appear to currently pose a threat to organizations. Most organizations with basic network security will simply block this type of traffic. Furthermore, the traffic is not concentrated enough on any single destination to be considered a large-scale DoS attack. So, why is it happening? Here, we can only offer speculative theories. Caution: these theories can provide new investigative directions, but in the end, only consistent evidence matters.

Cover for collection

Given the likely spoofed nature of the traffic, the originating party would only receive response data if they were in a position to collect the responses. Therefore, an actor would need to have some other listening capability to collect this spoofed traffic for scanning information. It is possible that some of the traffic is not spoofed and could hide in the noise, such that the actor would receive the responses from traffic sent by their actual infrastructure. So, either the actor has the ability to intercept responses, or this traffic could be providing a cover for actual scanning activity. However, this theory has holes. While May 2020 does seem an auspicious time to gain information about rapidly changing internet exposure, many other data sources already exist that could provide this information. Furthermore, why draw attention to SYN scanning by doing so much of it?

Poisoning threat intel

It is possible that this could be an effort to “poison” automated threat intel feeds by suddenly inundating them with millions of IP addresses purportedly performing scanning. In investigating some of these spoofed sources, we have seen them appear on recently updated blacklists and threat intel feeds. This is possible, but the scale of the activity is large enough to be unnecessary for this goal.

Testing

Much of what we have outlined above looks like potential testing. An initial spike occurs in January, followed by a lull in activity and then another “test” at the end of January. Later, sustained traffic occurs, with small tweaks appearing here and there. An actor with interest in deploying TCP spoofing for more destructive purposes could simply be testing their capability. The broad spread of distinct spoofed IPs does not create denial-of-service (DoS) conditions now, but that could change. It is possible that this is someone testing or demonstrating capability.

Recent activity and next steps

On April 30, May 1, and May 2 2020, we saw the highest levels of connections from this activity, followed by a sharp drop-off. Activity spiked again around May 8, but it has disappeared since then. Now that we have some rough signatures for what the traffic looks like, we are able to detect these spikes as they occur. Additionally, while it is impossible to confirm, we have seen some traffic which looks similar to this dating as far back as 2017, though not nearly at the levels seen this year.

Finally, a caveat: Our visibility through Heisenberg is by definition limited to our honeypots. While other organizations have corroborated these trends, we do not have a large amount of details on traffic being sent elsewhere.

The above theories are illustrative of what might be the intention here, but we do not currently have solid evidence to support a most probable theory, or eliminate others. Additionally, at the time of writing, we have no evidence to confirm that this presents an exigent threat. The simple fact is we do not know why this is happening, only that we are seeing it, it is new and strange, and other organizations have corroborated these trends. Given the unprecedented scope and volume, we felt it was worth publishing our research to begin a discussion among researchers, and hopefully understand this better.

Many thanks to Andrew Morris of GreyNoise and others in the community for providing information and feedback on this research.

![[QILIN] - Ransomware Victim: Mainetti 7 image](https://www.redpacketsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/image-300x300.png)